We loved this blog post so much that we snagged it (with their permission!) from our friends- Two Ravens. Dave Cowart wrote this one- be sure to check out the original post here!

There are plenty of articles proclaiming how great a place Birmingham has become. The food scene is world class! Shipt is showing what we’re capable of! The new mayor is going to fix everything! But nobody’s saying much about our disadvantages. Truth is, we have a lot—other cities have measurable leads in economic, educational, cultural, and societal measures. Our public image is shaded by the state as a whole. And regional cooperation is best measured under a microscope.

But don’t despair! In a bit of metaphorical judo, many of these disadvantages can actually be leveraged into advantages. One of the principles of judo is jū yoku gō o seisu, or “softness controls hardness”:

Resisting a more powerful opponent will result in your defeat, whilst adjusting to and evading your opponent’s attack will cause him to lose his balance, his power will be reduced, and you will defeat him. This can apply whatever the relative values of power, thus making it possible for weaker opponents to beat significantly stronger ones.

Instead of comparing ourselves to other cities and trying to emulate the paths they’ve taken, we should instead focus on what makes us unique and use our weaknesses as strengths. I’m not talking about finding the silver lining in a storm cloud; I mean actual, actionable changes we can make.

What are our greatest weaknesses? Size is an obvious starting point – we’re the 49th largest metropolitan area and the 104th largest city in the country. Population size isn’t everything, but it means we’re low on the list for outside investment, whether that’s attracting a corporate headquarters or a major sports team or even just niceties like the availability of same-day delivery or car-sharing. How do we use that as an advantage?

Since our city is smaller, we’re more likely to have friends in different industries. Sure, most people have lots of connections in their field, but we don’t have the density to support isolated bubbles like a financial district or a collection of tech campuses. This means that we’re more likely to be serendipitously exposed to the obstacles and breakthroughs of other industries, giving us the chance to treat our entire city like a huge Innovation Depot.

There are other advantages to being a smaller city. Cost of living is low, our worst commutes are laughable in other cities, and seeing familiar faces on the street can ward off the social isolation experienced by some people in large cities. The pace is a little slower, and people tend to be friendlier when there’s a chance you probably have a mutual friend. These factors can be crucial when recruiting against other larger population centers.

But why are we comparatively small? Growth in the metro area is slow, and it’s been getting slower for years. The city itself has actually been losing population. The good news is that we haven’t sacrificed our natural areas to develop real estate. Within a few miles of downtown, we’ve had Ruffner Mountain for decades and now we have Red Mountain Park. That doesn’t have to be the end of the story though. The same mountain that currently divides the city from its wealthiest suburbs has also shaped the city itself, both geologically and geographically, preventing sprawl in certain directions. Natural and historical areas in close proximity to downtown are still largely unspoiled and ready for enjoyment and preservation.

Industries that were previously a leading cause of the metro area’s growth are now declining or outdated. The steel industry has moved on, the financial industry has consolidated elsewhere, and we’re now home to only one Fortune 500 company. Those industries were the fuel that powered our economy and gave us the nickname “The Magic City,” and they occupied some of the prime real estate in town. They also employed many of the people that shopped and ate in the heart of downtown. Now that the furnaces and mills have closed and the shops and restaurants have moved away, all that land and empty real estate are available. The McWane Center and the Pizitz have revitalized empty department stores, Sloss Furnace is now a museum and the home to a successful music festival, Back Forty just opened a brewery/restaurant at the old Sloss Docks, and Amazon is building a fulfillment center on former U.S. Steel land. Just this week, DC Blox announced that they’re building a flagship data center at a closed steel mill a few blocks from UAB. It’s hard to imagine many other major urban universities having that kind of available land nearby. It’s important to focus on developing these previously-abandoned areas in a way that weaves young and innovative companies throughout the city.

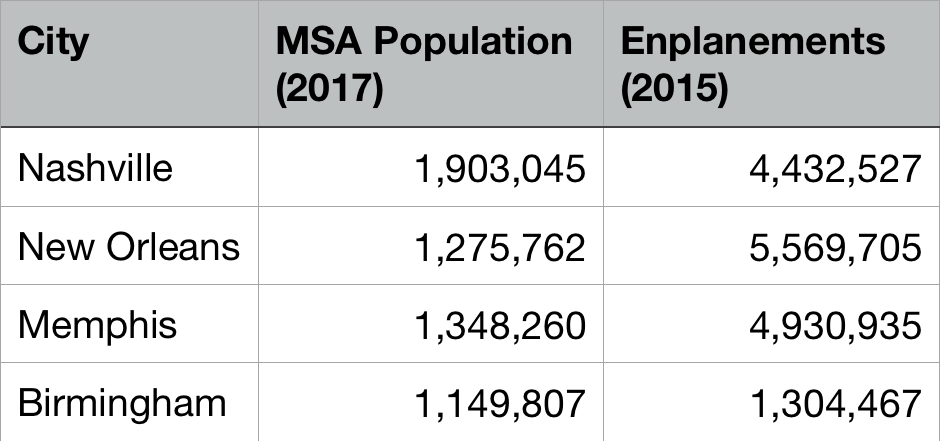

Our airport is substantially smaller than others in the southeast. Ignoring the behemoth to the east, it still sees just a fraction of the boardings as Nashville, New Orleans, and Memphis – cities whose metro areas aren’t that much bigger than ours.

Population vs. Enplanements (commercial boardings) by City

Tourism is a strong industry in those cities, but there’s clearly a lot of opportunity for growth. The good news is that people there who are looking at the future, realizing they have to innovate, and are already making plans. Enjoy the short security lines and easy parking while it’s not too busy.

Nobody on the outside is paying attention and expectations are low. It’s time to work together to leverage our disadvantages while still doing things our own way.